Billy Young and The Dead End Kids

Anthony Hill

Sandakan POW Families Oration

Canberra, 27 May 2011

I’d like to begin my talk this evening with a short piece of verse:

Where jungle canopy blocks sunlight from the ground,

Where towering mountain peaks lie covered in cloud,

Where foul black swamp and deadliness abound,

There – falling leaf and twig became their shroud.

These lines will be familiar to almost everyone who is associated with the Sandakan POW Families. They were written by our friend, Bill Young, the subject of my forthcoming biography, himself a Sandakan prisoner of war, whom you’re honouring tonight by making a patron of this organisation, together with another dear friend June Healey. Bill’s words have charged many an Anzac Day pilgrimage here at home – even more so in the tropic heat of a Borneo jungle, about which they were written, and where I first spoke them at a public gathering two years ago. Particularly the quatrain that follows:

From Sandakan they came away,

Stumbling on until they fell;

There along the track they lay

Leaving only six to tell.

Six. Botterill, Braithwaite, Campbell, Moxham, Short, Sticpewich. Only six survivors of the more than 2,270 prisoners of war who were alive at the infamous Sandakan labour camp at the beginning of 1945. Before that, an estimated 151 had already died of disease and maltreatment. At the start of that final year there were some 1,685 Australian and 592 British POWs, as Lynette Silver names them. Over a thousand died or were murdered by Japanese guards at Ranau or on the three death marches into the mountains that left between January and June, where ‘falling leaf and twig’ did indeed become their shrouds. The rest perished at Sandakan – left to forage, to die, to be slaughtered like animals in the open after their huts were burnt down in May. It was one of the greatest atrocities of the Second World War – a war of atrocities that left the English language almost bereft of adjectives to describe them adequately. Some 2,428 deaths altogether. We remember each of those brave souls this evening.

Bill Young with Nelson Short (left) and Keith Botterill (right), two of the six Sandakan death march survivors

But of course, of all those who were sent to Sandakan as POWs, many more than just six survived to tell the tale – or at least their part of it. And this is something that needs to be remembered. The numbers I’ve given – 2,277 men – refer only to those who were in the camp at the beginning of the final year. But before then more than 200 prisoners had been transferred – or more properly been deported – from Sandakan to Kuching: now the capital of Sarawak, then the Japanese administrative centre for all Borneo. And of those 200 plus sent to Kuching, the great majority managed to survive by the Grace of God.

By far the greater number were British and Australian officers sent away in four main groups from later 1942 through to October 1943. There were some 31 British and Leslie Bunn-Glover advises 144 Australian officers: among them the first Australian camp commander Lieut-Col. Alf Walsh, in charge of B Force, who’d distinguished himself by refusing to sign – except under protest – an oath not to escape. He was clearly a “trouble-maker” whom the Japanese commandant Hoshijima wanted to get rid of as quickly as possible.

There were other known trouble-makers, mainly rather youthful – indeed some under-age – Australian soldiers: high-spirited, anti-authoritarian, self-reliant young larrikins, forever on the scrounge and risking much. Admirable qualities, it would seem, for a prisoner of war at a place like Sandakan. Four of them sent to Kuching were from a group known as The Dead End Kids: which described not only attitudes among certain of their superiors as to the kids’ ill-disciplined character. In a physical sense they also lived at the “dead end” of the five rows of huts used by the Other Ranks in the Number One Sandakan camp: occupying the last room of the last hut down the hill and closest to the swamp. And it is these kids that I especially want to remember this evening.

Some 20 of the POWs sent from Sandakan to Kuching were those Officers, NCOs and Other Ranks arrested in July 1943 after the discovery of the secret radio, the underground network built up between the camp and the civilian population of Sandakan, and the contacts that had been made with resistance forces in The Philippines. As you know, the leader Captain Lionel Mathews was subsequently executed by firing squad, and the rest were sentenced to terms of solitary confinement in the horrific Outram Road Prison in Singapore.

There, they joined 13 or 14 other Sandakan men who’d actually succeeded in escaping from the camp – although they’d been eventually recaptured – shipped to Kuching – sentenced, and confined in Outram Road. With one exception they all survived the war. They were the lucky ones, though nobody would have said that at the time. But they, too, are survivors of Sandakan.

Among them is Bill Young – another of The Dead End Kids: a mere boy of 15 when he joined up in July 1941 – though he said he was 19, and nobody asked him for a birth certificate. The number of under-age soldiers who served in the Second World War is much greater than generally believed – as it is of the First World War. The official records are full of lies on the question of age. Indeed, the name of a fictitious aunt still appears as Billy’s next of kin on his enlistment form.

He was only 16 when sent to Sandakan with B Force after the fall of Singapore. And just 17 when he escaped with his older mate MP Brown in February ’43. They were caught after only a couple of hours on the track – viciously bashed into unconsciousness by the boiler house – kept in cages by the Kenpeitai, Nippon’s version of the Gestapo – and ultimately incarcerated in Outram Road. Forced to sit cross-legged at attention on a bare concrete floor for twelve hours or more a day; silent; for months in solitary; in a cell perhaps 12 foot long and 6 foot wide. You could touch the walls on either side … and feel them closing in.

Myles Peace (MP) Brown 1942

One wonders how anyone could survive this without going mad – as some Outram Road prisoners did – let alone a kid. It’s certainly the question that intrigued me, as a novelist. For Billy did survive by a combination of good luck, his native wit and intelligence, the survival skills he’d learned as a kid growing up around Paddy’s Market in Sydney during the Depression – not quite on the breadline, but close to it. By his strength of character. Not much by way of formal education, for he was a serial truant, but well-schooled in the wisdom of the streets. For him, the Kenpeitai and the prison guards were rather more virulent forms of school inspector.

And he survived the vicissitudes of both war and peace by one other quality that Billy might find it embarrassing for me to say – but which I think is nonetheless true and find quite fascinating.

Within the larrikin frame of this Dead End Kid there is the spirit of an artist. One that enabled him to respond to singing and to poetry. He sang with a group of youngsters in a small choir formed at Sandakan in those early months. He can still recite the poems scrawled on the walls of his prison cell. Kipling. Entirely self-educated, at a time in his mid-fifties when life seemed to be falling apart, he taught himself to paint. To write down his story in a book which became Return To A Dark Age. And to write his own poems of war and suffering which express not only himself, but as I said keep alive and vibrant the memory of his own dear friends from the Dead End Kids hut – and through them all who shared the experience of Sandakan, and what it means. Art was his salvation.

You cannot tell a battlefield

Once the dead are buried;

Once the birds return again;

Once the flowers bloom.

And once time absorbs the pain.

I came across Billy’s story some years ago here in Canberra, where I live. Several Sundays a month I have a stall at our arts and crafts market at Kingston’s Old Bus Depot, selling my books and meeting readers. A lady buying one of my military stories one day said, ‘You should write a book about my husband’s Cousin Bill.’ Now, a lot of people say I should write about their Cousin Bill; but this one stayed in my mind. Nearing the end of a novel on Captain Cook and the Endeavour, it seemed ever more urgent to find him.

I tracked Billy down in Sydney with the assistance of Sheila Bruhn, (Allen) whom some of you may know; rang him with a degree of trepidation, for you never know if a subject will respond with hostility. But as anyone will testify, the first question to this Cousin Bill prompted a flow of story down the telephone that culminated with ‘Do you know what the older blokes who looked after me called me? Billy The Kid.’ There was a title! And I knew at once I had a book.

Since then Bill and I have spent close to 100 hours – together or on the phone – talking over his childhood, fleshing out his wartime experience in Malaya, Singapore and Sandakan as recounted in Return To A Dark Age, and reviewing his later life, to the point where I’m sure he is sick of the sound of my voice. It’s been a long haul, but I hope readers will think it’s been worth it when our book comes out with Penguin – probably under the simple title of Billy: Changi–Sandakan–Outram Road – early next year.

For myself, I found his early years growing up as a working class kid during the Depression of particular interest, as an aspect of our social history. I’ve always wanted to write a market book, and this is it. Bill rarely touches on it in his book – and time doesn’t permit me to go into it here, other than to make the point that it taught him skills to draw on as a POW. Learning to live by his wits. Alive to any little opportunity that came his way. Alert to any passing copper.

Bill – Keith William Young to give his full name – was born in Hobart on 4 November 1925, and was always told that his mother had died when he was still an infant. His father, Big Bill Young, took the boy to Sydney, where he eventually came under the care of Pop and Ma Jepson, a couple of old circus performers, who had a fruit stall at Paddy’s Market and ran a boarding house in Ultimo. They took in father and son, and indeed taught the boy the tricks of his trade.

Big Bill had always lived something of an erratic, itinerant life. Until, like many people shocked by the despair of Depression, he was converted to the Communist Party. In 1937 he stowed away on a ship bound for England, and from there went to Spain to fight the Fascists in the civil war. Where he was killed on the Ebro the following year – one of 14 or 15 Australians to die in Spain – and the boy really was alone. He left school as soon as he turned 14; got a job delivering telegrams on his bike; and in 1940, after War broke out, Billy even tried to join the Navy. Passed the test, too. But they did find his Birth Certificate, and wrote a stern letter of rebuke.

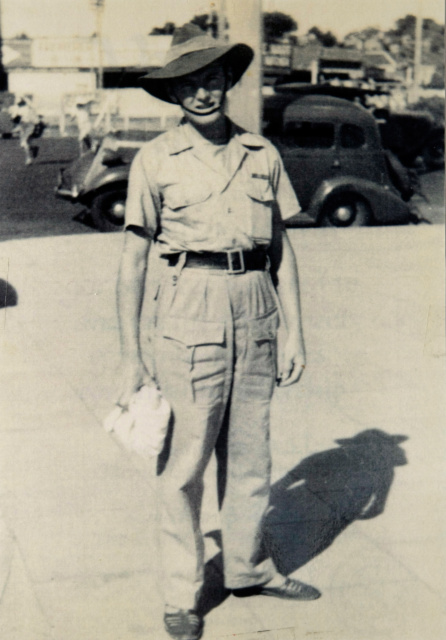

Billy's father 'Big Bill' Young aged 15.

If his country didn’t want him…! The kid and a mate Donny set off to ride around Australia, odd-jobbing along the way But they only got as far as Mount Gambier, when the Billy’s bike broke down completely. Penniless, homeless, they hitched back to Melbourne in July ’41, where Don suggested they join the Army which offered a feed, a blanket, and five bob a day. The problem of the consent form was solved on the writing desks in the GPO next door … and by the fictitious aunt. Martha Young. It was the only female name he knew how to spell.

Well, Billy was assigned to the reinforcements of the 2/29th Battalion, about to depart for Malaya. He was there himself 10 weeks later, in training at Tampoi near Johore; and was still there when the Japanese attack came that 7 December. Like everyone, shocked by the speed and overwhelming success of the Japanese thrust down both sides of the Peninsula. By mid January ’42 they were closing in on Johore; and despite the gallantry of the Australian battalions at Gemas, Muar, Parit Sulong and Jemaluang, they only managed to slow them down for a few days.

When Billy Young joined his battalion on Australia Day ’42, as it was being re-formed after having lost half its strength, the end was pretty clear. Yet the kid was one of the better-trained reinforcements. Thousands of replacements continued to arrive in Singapore, some of them raw recruits who’d barely been in the army a month. Not at all surprising, when the Japanese crossed the Strait at a point held by the Australian Brigades, that the thinly-stretched defences broke. Within days the Allied Divisions were forced back upon the city. Confused. Outflanked. Demoralised by a failure of leadership at the highest level.

Billy’s company, like many others, became separated during a night retreat. Platoons and sections were split from each other. The kid himself was wounded by a shrapnel splinter in the thigh, his feet cut to ribbons when he lost his boots. He was even sent to hospital on the last day before surrender on 15 February. Yet luck was with him. He chose the correct ambulance. The other would have taken him to Alexandra Hospital, where over 150 patients and staff were massacred the next day.

Bill and Paddy O'Toole in later life

Lucky, too, in the men of his section. In Paddy O’Toole, ‘The Wild Irishman’, a natural leader, who became like an older brother to the 16-year-old. And in his Lance-Corporal, Bob Shipsides, then 32: a bushman from Dimboola, another born leader, who worked with Paddy O’Toole as a hand fits in a glove. They were both independent, sturdy souls, who took no nonsense from anyone, and would as soon tell an officer to get stuffed if they thought orders were foolish. Bob gained and lost his stripes with some regularity, though he was always “The Corp.”

When Billy arrived at Changi from the hospital as a POW, he found that Bob Shipsides was gathering around him in the rather looser arrangements of Selarang Barracks, a group of similar congenial spirits drawn not just from the 2/29th, but from several different units.

A few older men in their twenties. Keith Gillett, a shearer’s cook, who once made a “surprise stew” from chef Two Ton Tony’s pet monkey; one of the few privates given permission to marry a Malay girl who was carrying his child, and The Shearer carried her photo constantly with him. Jimmy Brown – M P Brown – Myles Peace, because he was born on Armistice Day 1918, though nobody ever called him that. “Peace” in the middle of a war? The 24-year-old Queensland timberman would have flattened them. Brownie was married too, with an infant daughter; a man of remarkable natural gifts with an ear for music and language. He played the fiddle and harmonica, serenading many a night at Changi and Sandakan; taught himself to speak Malay, Dutch and Japanese from those around him. It’s one of those pities that Brownie wasn’t able to develop his talents as they deserved, through the circumstance of War and Depression.

So there were these older men. But Shipsides was also gathering around him a number of younger soldiers – some of them still under-age, like Billy, who was only 16. Bringing them under his protective care, like a mother hen her chickens, and who, when most of them were sent to Sandakan with B Force in July, became the nucleus of The Dead End Kids.

Kids like Joey Crome, who claimed to be 22 but in fact was perhaps nine months older than Billy, whose father ran the picture theatre at Bondi Junction. The two were very close. Indeed, during the voyage to Sandakan in that hell ship Yubi Maru, the two found themselves hiding on deck one night anchored off Miri, the lights of the town beckoning across the velvet water, remarking that it didn’t look very far to swim. ‘In you go then…’ ‘You’re the kid from Bondi! You go first.’

Joey Crome with his sister in Sydney, 1941.

Fortunately neither of them took the plunge. For just then the cook appeared and threw a bucket of scraps overboard. At once the sea began to swirl with phosphorescence as fish fought to feed – and one huge, gaping mouth of serrated teeth that lunged from the deep to consume the lot.

There was Wally Ford from Hobart – “Henry Ford” everyone called him for obvious reasons of name play – who said he was 21, but in truth was much younger; always with his rather lop-sided, boyish grin.

And then there was Harry Longley, a farmer’s son from Yass, just north of the border here in NSW. Harry was only 17 when he enlisted in 1940, though again he claimed to be 21: born in 1919. How careful, one thinks, these youngsters must have been remembering to write down the wrong birth year on their enlistment forms. Believing the lie implicitly whilst they were telling it.

In many ways Harry was the leader of these younger blokes. Slightly older than them, he had a countryman’s experience of knowing what to do in an emergency. Billy tells a wonderful story of the hiatus of about a week on Singapore, when the Japanese garrison was being changed over and the guards disappeared. The prisoners found themselves free to go out on the scrounge; and passing through a village one day with a bunch of coconuts, the two found themselves approaching a group of Japanese soldiers sitting outside a café.

‘What are we gunna do, Harry?’ ‘Give em an “Eyes Right”, and keep on marching.’ Which they did, smartly at the salute. And to the boys’ astonishment, the Japs returned it: rising at their tables, snapped to attention, and watching their prisoners carry on down the road.

Harry Longley, 1941 (courtesy his brother, Gerald Longley).

It didn’t last, of course. The horrors of becoming a POW under Nippon at Changi reimposed themselves. A Force, and later F Force, which included Paddy O’Toole, were sent to the Burma-Thai Railway, from which over a third – one in three – did not return. B Force, and then E Force were sent to Sandakan, of which fewer than one man in 14 survived: and of those, all but six were among the 200 or so transferred to Kuching or Outram Road, as I’ve mentioned.

Yet in those early days at Sandakan, Harry Longley was always out front of those young fellers that came to be known as The Dead End Kids … sharing with Bob Shipsides and his group that last room of the last hut in the row closest to the swamp and the barbed wire fence.

There were 14 in the room, sleeping side by side on a raised wooden platform on either side. Billy by the door on one side, and next to him M P Brown. Joey Crome and Longley. The Corp of course, and Shearer Gillett. Wally Ford and another young soldier, Jimmy Finn of the 2/30th Battalion. He was only a relatively small feller – about 5’ 6” – but nuggetty and muscular, and a champion boxer … a bantamweight, with a steam-hammer fist. “The Pocket Atlas” Billy calls him, and so he was, and demonstrated it at the boxing matches the Japs would sometimes allow to be staged at nights in the compound.

He wasn’t the only skilled boxer in the room. John Bryant – “Snowy” Bryant of the 2/18th, then in his early 20s, slim and fair, had been fighting preliminaries in the professional ring from a youth. No heavyweight, he was still considered a fighter to be reckoned with. It’s an interesting sidelight on the Depression years, in fact, how the ring was so often seen as a way out of poverty for young working class men. In any event, a bout was arranged at Sandakan between Snowy Bryant and Jimmy ‘Punchy’ Donohue. It was billed as a ‘grudge match’ – and excitement built up for weeks. Both boxers went into a strict regime. A punching bag was installed under the hut, skipping ropes provided, and men came from all over camp to see the opponents working out. If I may read the passage from my book:

“Gunboat Simpson [Corporal Henry Simpson from a neighbouring hut] appointed himself Punchy’s trainer, and Keith Gillett took over Snowy’s management. The Shearer also ran the book, betting heavily on his man, and he seemed set to clean up royally. On the night – as hot and thick with the smell of blood as any evening in the Tin Shed at Rushcutter’s Bay – Snowy Bryant danced rings around Donohue. Punchy was the younger bloke, but he’d been on the Tin Shed’s canvas too often. His eyebrows were split, he seemed to walk on the back of his heels, and was altogether slower than the nimble Bryant.

“For two and a half rounds Snowy outclassed his opponent. A jab here. A volley of blows there. Keith Gillett was already counting himself a millionaire. When, just as the bout was ending, Punchy found the resources to land a massive uppercut on Snowy’s jaw. Bryant went down – and out for the count, himself. The crowd went wild. The Shearer went into bankruptcy and into hiding: emerging a few days later offering to pay one cent in the dollar. After the war.”

There was no reneging on debts at the pontoon school Gunboat Simpson ran at nights beneath his hut. It was quite high under there, men sitting in a ring round a depression in the earth where a big tree had once stood, screened from view by a curtain of old blankets and atap, and lit by a globe let down through the hut floor. Minimum entry was a 10 cents stake, with Gunboat sitting at the entrance to make sure you had it. It was a hard enough sum for the kids in the dead end hut to scrape together; but whenever they did, the game was always for one of them to go in first, show Gunboat his money, and sit down by the outer curtain … pass his 10 cents under the blanket wall to a cobber on the other side … who’d show his money to Gunboat … enter … and repeat the exercise. Billy says Gunboat would have killed them had he found out. But he never did.

Who else was there among The Dead End Kids? Terry Risely from Tasmania – properly Jack Hilton Risely, though “Hilton” like “Myles Peace” was not a name that was spoken. A Queenslander known as “Cookie”, whom I haven’t been able to track down, but whose life was saved when a Japanese sword meant to behead him was miraculously deflected. His neck scars were a matter of intense interest to the youngsters.

Trevor Dobson, “Tassie Dobson”, another young soldier from the Apple Isle, who serenaded through many a night on the verandah, beating on a box drum while Brownie played his harmonica, singing a favourite song about the Ringle-Rangle Ram. A couple a blokes from Wagga Wagga – Sid Outram and Jim Donohue – who’d enlisted together and were the closest of mates.

Sid Outram in fact was one of the Dead End Kids sent to Kuching and who survived the War. Yet he always mourned the loss of his mate. In later life Sid turned rather inward and reclusive. So many did. But Billy tells a most poignant story of once persuading Sid to come out to the club at Wagga for a drink, and of how the old bloke’s eyes ran with tears as they sat singing Tassie Dobson’s song:

Hi ringle-rangle, hi ringle-ray,

He was the finest ram, sir,

That ever was fed on hay.

Such is the power of music to evoke the past and to move our souls.

None of this is to detract from the brutalities suffered by the 1500 men of B Force – later to be joined by some 500 men of E Force and over 770 British POWs, to say nothing of thousands of impressed native civilians – as they laboured to build the airfield a mile away from the Sandakan camp. The labour with heavy changkol and basket to move the tufa soil – a gelid, sloppy blancmange in the wet, so blinding white in the sun men had to make eyeshades from small bamboo sticks – to level the runway. The sudden assaults by guards armed with clubs and wooden swordsticks to punish some small infraction … for not working hard enough or for nothing at all. The group punishments known as “Flying Practice” … standing for hours in the heat with arms outstretched, and a bashing if they dropped even slightly. “I made it to sergeant today. Three stripes.” The sick forced from their beds with kicks and blows to work. Even some of the officers, eventually.

'Flying Practise' by Bill Young

All of this is true. But nevertheless, in that first year or so the POWs were permitted their small diversions. Sing-songs. Boxing. The satisfactions, when the Nips decided not to put drains across the airfield, of seeing a steamroller sink slowly into the bog, the skips used to cart the earth suddenly veer off the rails. They put drains in eventually. And, too, for so long as the Japanese required a strong workforce, food supplies were at least basically adequate: one and a half pounds of rice a day for those doing heavy labour, one pound for the rest, supplemented by small amounts of meat ,and vegetables grown by the officers. Even a dugong once or twice, as a gift. Much less was given to the sick: which was probably intended as retribution or a hurry up, but it only made them weaker and even more unable to work.

Of all the ways by which supplies were added to, none were more important than the scrounge. Tapioca. Yams. Coconuts. Whenever such things could be found outside and smuggled back into the camp, full bellies were always worth the risks of being caught. And of all these scroungers, none were better at it than the Dead End Kids. A double wire perimeter fence across the swamp was close to their hut, overlooked by a boardwalk and a couple of watchtowers, though the guards rarely seemed to go there. It was not all that long before the youngsters had managed to cut a hole in the wire beneath the swamp water through which they could wriggle like eels, attach a guideline from under their hut to the boardwalk piers, and in groups of twos and threes sneak out at night to forage down jungle paths and to the outskirts of native kampongs, or villages. Returning with haversacks replete, they’d wait in the water for a signal down the lifeline: one tug to say ”all clear”, two tugs for “danger.”

Bob Shipsides and the wiser heads always counselled caution. “You silly young buggers, you be careful.” But they never declined the tapioca chips, coconuts, an occasional bit of meat, wild fruits and cigarette weed made from banana or pawpaw leaves that followed a successful expedition.

Their warnings were well-based. Four times in the seven months he was at Sandakan, Billy was caught by the guards Once he was discovered smuggling tapioca roots into the camp hidden in a load of firewood – for which he’s always blamed one of the officers for giving a tip off – and was locked in a wooden punishment cage a mere five feet long and four feet high. Again, he and Joey Crome one day tagged onto a work party emptying toilet buckets into the swamp. While the dunny party trudged back and forth to the camp, the boys ducked off down a track, returning with a chicken in their own buckets. But they were caught just as they were entering the gates, by a guard who happened to be counting the numbers – were knocked senseless by a particularly vicious guard known as The Black Bastard – and again were locked for two days in the hot box.

Some things were beyond the kids’ experience. He and Joey Crome went out one night with Punchy Donohue, but quite unexpectedly ran into a group of Japanese guards on the jungle track. There were shouts and shots. The youngsters separated; and by the time Billy and Crome made their way back to the swamp they saw the camp was alive with activity, lights blazing and the guards actually sitting on the boardwalk over the water talking of what mincemeat they’d make of the prisoners when caught. It took an hour or so for the young fellers to make their way underwater, using the coconuts in the haversacks as floats, swimming beneath the guards’ very feet, through the wire and back to the hut. Where an officer arrived to say that Donohue had been caught, and unless the two presented themselves immediately he’d be executed.

They found him in the hands of the Black Bastard and the camp interpreter Ozawa, a small man nick-named “Jimmy Pike”, after the jockey. He seemed genuinely bemused. “You men got out of camp, even though I had guard to stop you? You then got back into camp even though I had trebled the guard to stop you?” The kids thought “ This is it.” But instead Jimmy Pike said softly, “You go now,” and began laying into the Black Bastard – who passed it down the line – for having let the prisoners slip through his fingers.

One can quite understand the concerns of the officers that such antics could put the safety of the whole camp at risk. But these Dead End Kids were young – had no great thought of consequences – and besides were always harbouring dreams of escape. Harry Longley had found a small cavern in a rock outcrop by the Sibuga River a couple of miles away, and under his supervision the youngsters were collecting supplies for an escape when they could find a native boat. Billy had a map torn from an old school atlas in Singapore, and it didn’t look far to sail to Australia! Just round the top of Borneo – past New Guinea – and into Darwin. Ignorance being bliss.

The trouble was that metal rusted and food went bad in the tropical heat. And it was while trying to obtain some long-lasting dried Japanese cooked rice, that Billy Young and M P Brown attempted their escape in February ’43. Brown had agreed to help Billy talk to a local village man one lunchtime – but returning to the airfield they saw they’d already been missed. Heads were being counted. Two days earlier they’d witnessed the terrible bashing and torture of an Aboriginal man named Jimmy Darlington – another fine boxer – who’d knocked down one of the guards. Knowing what would happen to them, Billy and M P made their own break. But as I said, they were caught after only a couple of hours on the track heading towards the riverside cavern. Were bashed senseless. Interrogated by the Kenpeitai. And eventually sentenced to Outram Road Prison, Which, as it turned out, saved their lives.

The torture of Jimmy Darlington by Bill Young

They were the only two among the Dead Enders to try to escape Sandakan. Though not the only two to survive. Four of the 14 managed to do so – a very high ratio – and it might have been six had fate decided otherwise. For at the very time in June ’43 that Billy and MP were being tried in Kuching, another four from the Dead End Kids hut were arriving from Sandakan. Terry Risely and Sid Outram. Joey Crome and Wally Ford. So, too, was “Mo” Davis, in charge of the Sandakan boiler-house – a key figure in the underground network, and another trouble-maker – sent down to Kuching with 17 officers. In fact “Mo” saw Billy, Brown, and five other recaptured escapees led by Alan Minty being loaded in a horsebox onto the ship that bore them to Singapore and Outram Road Prison.

“Mo” Davis, Terry Risely and Sid Outram remained with the officers in Kuching, and so survived. The Japanese were planning to massacre them at the end – to “annihilate them all and leave no traces” as the orders put it – but the Allies reached Kuching before they were put into execution, and thus the prisoners were saved. The others were not so fortunate. Joey Crome and Wally Ford couldn’t stand Kuching, and volunteered to join 300 mainly British POWs sent to the island of Labuan to build another Japanese airfield. There both Crome and Ford died of disease, malnutrition and overwork. Two thirds of them did so. In March 1945, the remainder were transferred to the Borneo mainland; and in June, the 44 who then still lived were massacred near Miri.

It was a reprise, on a smaller scale, of the atrocities that befell the 2,270 men left at Sandakan. The accumulating horrors as 1944 turned into 1945. The brutalities. The mounting death toll. Rice rations reduced to a mere few ounces a day, and then to nothing, though there were tons stored at Hoshijima’s house. No more pontoon games. No more boxing matches. No more sing-songs. The beginning of the death marches. The huts burned down at the end of May – which we remember at this time. The survivors herded into the open to die. Or be murdered. The last man was beheaded on the day the war ended, and Sandakan camp abandoned. Time does not permit me to speak of these things in detail, and others have done so better than I.

But what of the eight who were left in The Dead End Kids hut? Their names all appear on the rolls of the dead. The boxer Snowy Bryant at Sandakan in March of malaria, and also Keith Gillett, The Shearer, of beriberi at Ranau, having survived the first death march. Jimmy Donohue, Sid Outram’s mate, also died at Ranau. Bob Shipsides, The Corp, died at Sandakan in April, apparently from malaria. Cookie and Trevor Dobson too, died of malaria at Sandakan it is said, but you can’t be certain because the cause of death was often falsified on Japanese orders. Harry Longley, who was on the second march, is stated to have died of malaria at Ranau in July – but both Keith Botterill and Nelson Short, two of the six who survived the death marches and who were there, told Bill Young in later years that his dear mate collapsed on the track while out with a work party. They propped him against a tree; gave him a fag; and moved on, listening for the sound of the shot from a guard’s rifle. “Harry’s had his last cigarette.”

The last of them, Jimmy Finn, the “Pocket Atlas”, laid down the burden of the world at the very end of the war … after the war had ended, indeed. Having survived so much, he was with the last group of 10 Other Ranks to be massacred by the Japanese at Ranau. Shot down in cold blood. According to official records it took place on 9 August; but Lynette Silver argues strongly that it actually happened on 27 August – 12 days after the Japanese surrender; the same day that the last five surviving officers were also murdered.

Scratch beneath the layers of those years.

Seek to find the reasons for our tears.

Unearth the splintered bones and rotting gear.

Uncovered, the horror of massacres appears.

With these lines of Bill Young, let us remember and honour them all again this evening: those men that I have spoken of, and their two and a half thousand brothers whose names and faces … whose reality, still lives in the hearts of every one of you. It is only when we think of them in all their individual humanity – as sons, husbands, fathers, as members of all the Sandakan Families – with their strengths and failings, their capacity to love and laugh and suffer and endure – that the truth that lies behind the statistics of Sandakan makes itself felt. It is said that Bob Shipsides’ mother kept the light on in his room every night until she died, for the time her son would come home.

Bill Young home in Hobart, November 1945

For these men are also part of the human family. As we consider their sacrifice, let us think of what might have been. Not all who came home of course taught themselves to paint pictures or write poetry. But every one of us has the ability to grow, to learn, to fulfil something worthwhile to the world in whatever field of life our interests may be. A capacity for expression and yearning after the divine cut short, for those who did not return, by the horrors of war and the tragedies of Sandakan.

The boiler’s dry, the fire’s out,

The years have laid the ghosts about,

With only now and then a sigh –

A whisper from the past – of Why?

Poems from My War In Pictures, My Thoughts in Verse by Bill Young